# Another Example

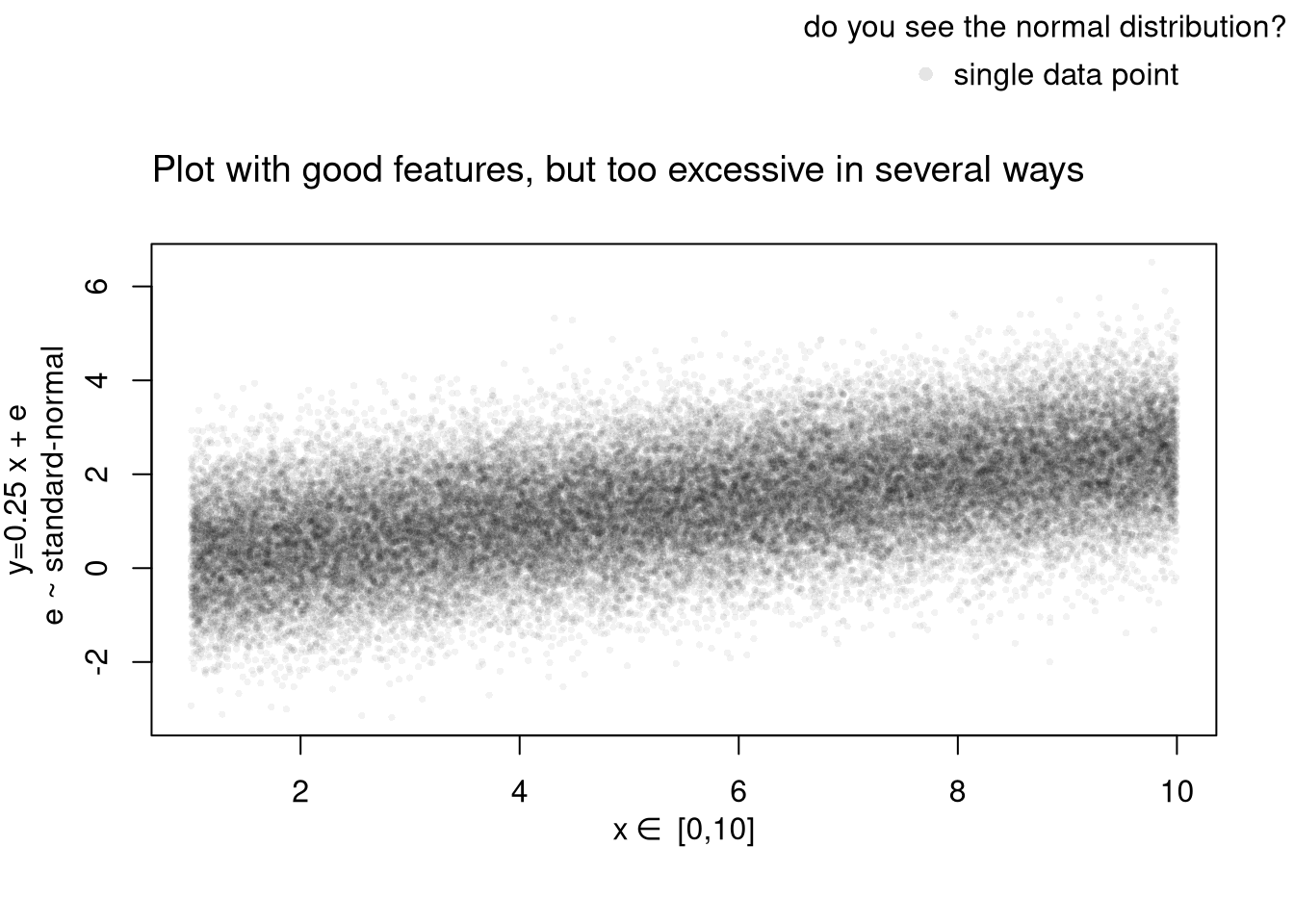

xy_dat <- data.frame(x=x, y=y)

par(fig=c(0,1,0,0.9), new=F)

plot(y~x, xy_dat, pch=16, col=rgb(0,0,0,.05), cex=.5,

xlab='', ylab='') # Format Axis Labels Seperately

mtext( 'y=0.25 x + e\n e ~ standard-normal', 2, line=2.2)

mtext( expression(x%in%~'[0,10]'), 1, line=2.2)

#abline( lm(y~x, data=xy_dat), lty=2)

title('Plot with good features, but too excessive in several ways',

adj=0, font.main=1)

# Outer Legend (https://stackoverflow.com/questions/3932038/)

outer_legend <- function(...) {

opar <- par(fig=c(0, 1, 0, 1), oma=c(0, 0, 0, 0),

mar=c(0, 0, 0, 0), new=TRUE)

on.exit(par(opar))

plot(0, 0, type='n', bty='n', xaxt='n', yaxt='n')

legend(...)

}

outer_legend('topright', legend='single data point',

title='do you see the normal distribution?',

pch=16, col=rgb(0,0,0,.1), cex=1, bty='n')