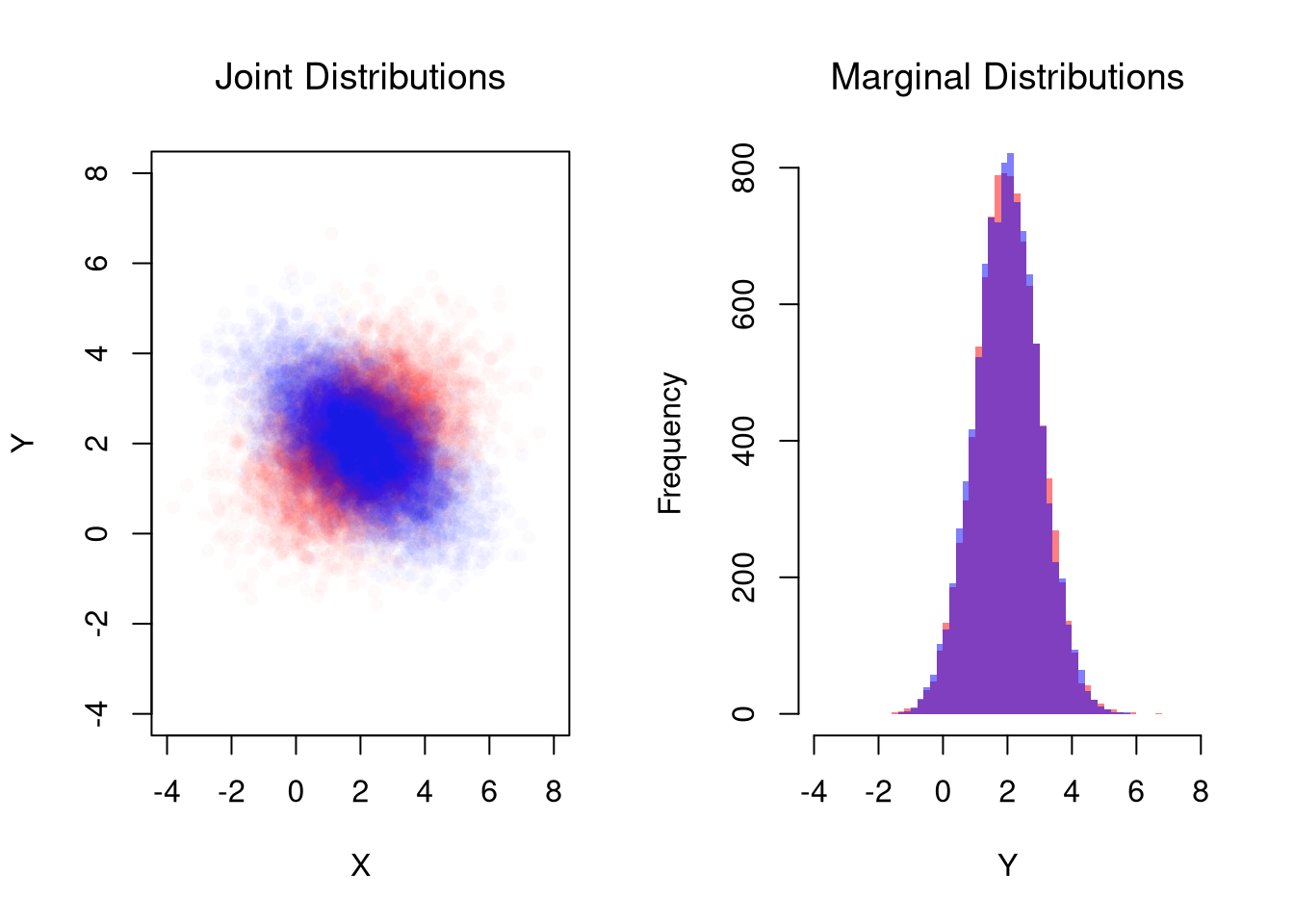

# Simulate Bivariate Data

N <- 10000

Mu <- c(2,2) ## Means

Sigma1 <- matrix(c(2,-.8,-.8,1),2,2) ## CoVariance Matrix

MVdat1 <- mvtnorm::rmvnorm(N, Mu, Sigma1)

colnames(MVdat1) <- c('X','Y')

Sigma2 <- matrix(c(2,.4,.4,1),2,2) ## CoVariance Matrix

MVdat2 <- mvtnorm::rmvnorm(N, Mu, Sigma2)

colnames(MVdat2) <- c('X','Y')

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

## Different diagonals

plot(MVdat2, col=rgb(1,0,0,0.02), pch=16,

main='Joint Distributions', font.main=1,

ylim=c(-4,8), xlim=c(-4,8),

xlab='X', ylab='Y')

points(MVdat1,col=rgb(0,0,1,0.02),pch=16)

## Same marginal distributions

xbks <- seq(-4,8,by=.2)

hist(MVdat2[,2], col=rgb(1,0,0,0.5),

breaks=xbks, border=NA,

xlab='Y',

main='Marginal Distributions', font.main=1)

hist(MVdat1[,2], col=rgb(0,0,1,0.5),

add=T, breaks=xbks, border=NA)