Code

statistic <- function(X, f){

y <- f(X)

return(y)

}

X <- c(0,1,3,10,6) # Data

statistic(X, sum)

## [1] 20We often summarize distributions with statistics: functions of data. We will go through some specific examples mathematically below, but can intuitively understand that they are generally computed as statistic <- function(x){ .... }.

The most basic way to compute statistics is with summary, which reports multiple values that can all be calculated individually.

# A random sample (real data)

X <- USArrests[,'Murder']

summary(X)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.800 4.075 7.250 7.788 11.250 17.400

# A random sample (computer simulation)

X <- runif(1000)

summary(X)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.001442 0.250637 0.509871 0.501544 0.742488 0.999849

# Another random sample (computer simulation)

X <- rnorm(1000)

summary(X)

## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## -3.39150 -0.69232 0.01046 -0.01267 0.63230 3.09302Together, the sample mean and variance statistics summarize the central tendency and dispersion of a distribution. In some special cases, such as with the normal distribution, they completely describe the distribution. Other distributions are better described with other statistics, either as an alternative or in addition to the mean and variance. After discussing those other statistics, we will return to the two most basic statistics in theoretical detail.

The mean and variance are the two most basic statistics that summarize the center and how spread apart the values are for data in your sample. As before, we represent data as vector \(\hat{X}=(\hat{X}_{1}, \hat{X}_{2}, ....\hat{X}_{n})\), where there are \(n\) observations and \(\hat{X}_{i}\) is the value of the \(i\)th one.

Perhaps the most common statistic is the empirical mean, also known as the sample mean, which is the [sum of all values] divided by [number of values]; \[\begin{eqnarray} \hat{M} &=& \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\hat{X}_{i}}{n}, \end{eqnarray}\] where \(\hat{X}_{i}\) denotes the value of the \(i\)th observation.

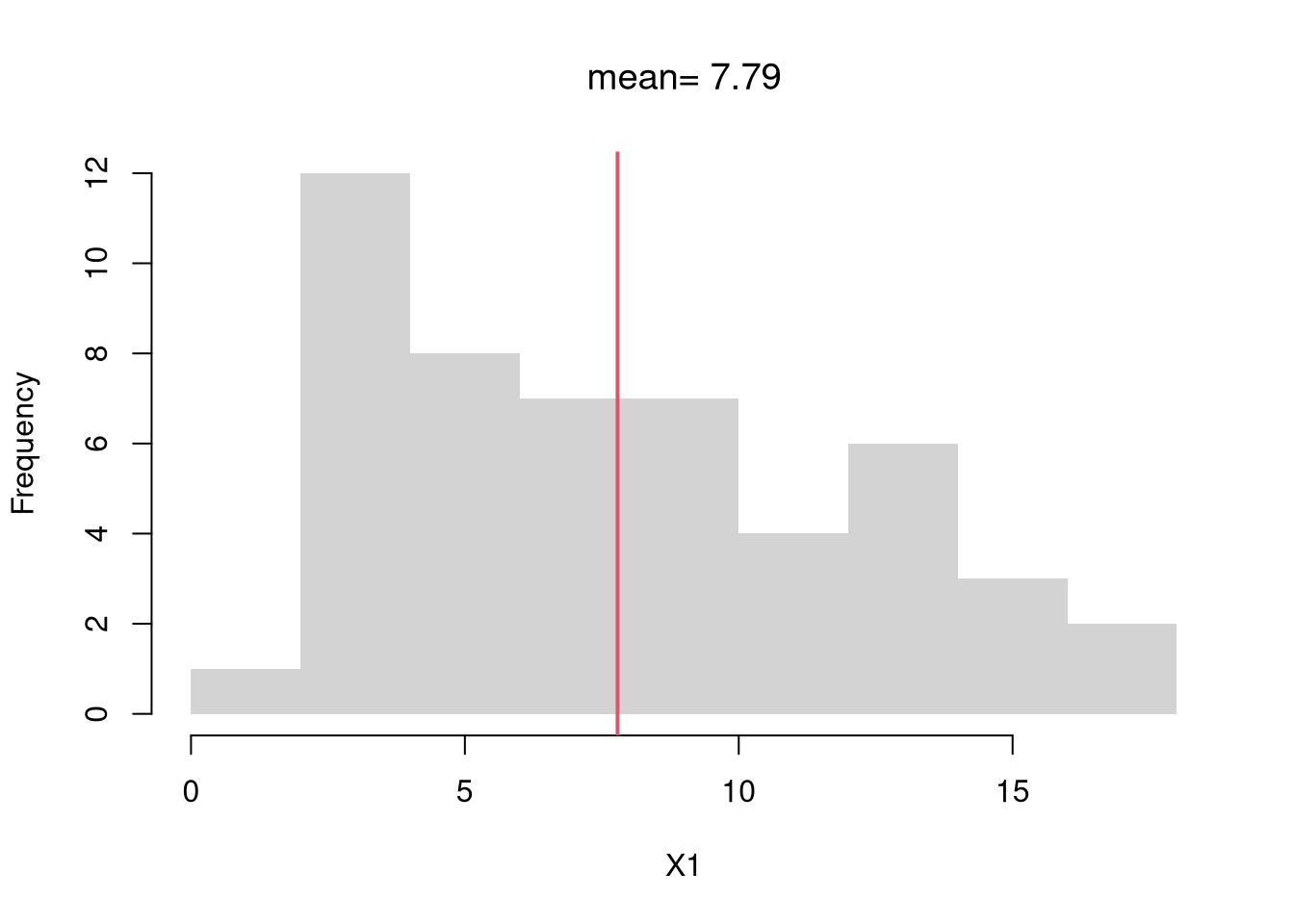

# compute the mean of a random sample

X1 <- USArrests[,'Murder']

X1_mean <- mean(X1)

X1_mean

## [1] 7.788

# visualize on a histogram

hist(X1, border=NA, main=NA, freq=F,)

abline(v=X1_mean, col=2, lwd=2)

title(paste0('mean= ', round(X1_mean,2)), font.main=1)

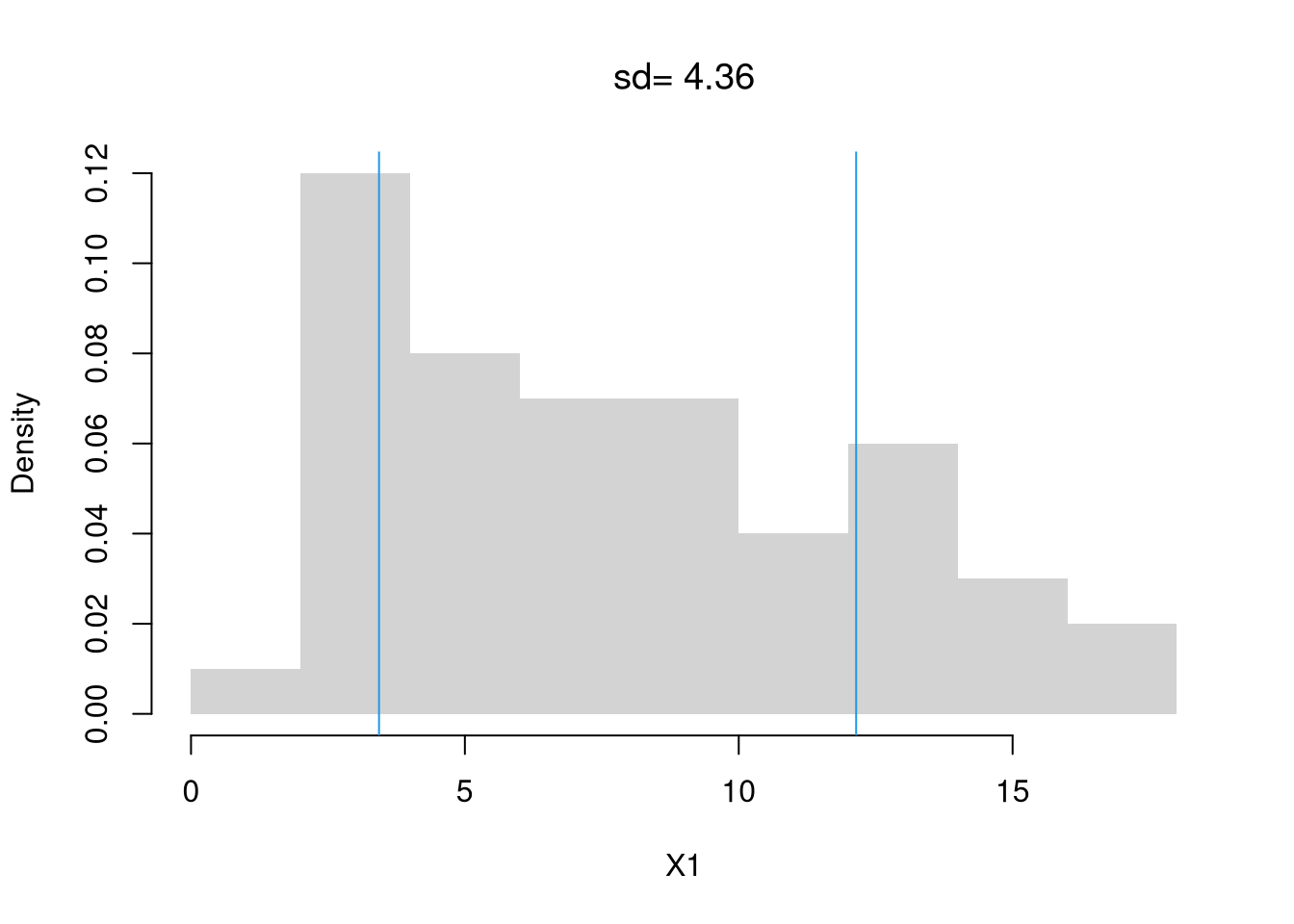

Perhaps the second most common statistic is the empirical variance: the average squared deviation from the mean \[\begin{eqnarray} \hat{V} &=&\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} [\hat{X}_{i} - \hat{M}]^2}{n}. \end{eqnarray}\] The empirical standard deviation is simply \(\hat{S} = \sqrt{\hat{V} }\).

X1_s <- sd(X1) # sqrt(var(X))

hist(X1, border=NA, main=NA, freq=F)

X1_s_lh <- c(X1_mean - X1_s, X1_mean + X1_s)

abline(v=X1_s_lh, col=4)

text(X1_s_lh, -.02,

c( expression(bar(X)-s[X]), expression(bar(X)+s[X])),

col=4, adj=0)

title(paste0('sd= ', round(X1_s,2)), font.main=1)

A general rule of applied statistics is that there are multiple ways to measure something. Mean and Variance are measurements of Center and Spread, but there are others that have different theoretical properties and may be better suited for your dataset.

We can use the empirical Median as a “robust alternative” to means that is especially useful for data with asymmetric distributions and extreme values. Recall that the \(q\)th quantile is the value where \(q\) percent of the data are below and (\(1-q\)) percent are above. The median (\(q=.5\)) is the point where half of the data is lower values and the other half is higher. This implies that median is not sensitive to extreme values (whereas the mean is).

X1 <- USArrests[,'Murder']

median(X1)

## [1] 7.25

quantile(X1, prob=0.5)

## 50%

## 7.25We can also use the sample Interquartile Range or Median Absolute Deviation as an alternative to variance. The difference between the first and third quartiles (quantiles \(q=.25\) and \(q=.75\)) measure is range of the middle \(50%\) of the data, which is how the boxplot measures “spread”. The median absolute deviation is another statistic that also measures “spread”. \[\begin{eqnarray} \tilde{M} &=& \text{Med}( \hat{X}_{i}) \\ \hat{\text{MAD}} &=& \text{Med}\left( | \hat{X}_{i} - \tilde{M} | \right). \end{eqnarray}\]

IQR(X1)

## [1] 7.175

mad(X1)

## [1] 5.41149The mean generalizes to a weighted mean: an average where different values contribute to the final result with varying levels of importance. For each outcome \(x\) we have a weight \(W_{x}\) and compute \[\begin{eqnarray} \hat{M} &=& \frac{\sum_{x} x W_{x}}{\sum_{x} W_{x}} = \sum_{x} x w_{x}, \end{eqnarray}\] where \(w_{x}=\frac{W_{x}}{\sum_{x'} W_{x'}}\) is normalized version of \(W_{x}\) that implies \(\sum_{x}w_{x}=1\).

When data are discrete, we can also compute the mean using “probability weights” \(w_{x} = \hat{p}_{x}=\sum_{i=1}^{n}\mathbf{1}\left(\hat{X}_{i}=x\right)/n\).

In principle, we can also compute other weighted statistics such as a weighted median.

Central tendency and dispersion are often insufficient to describe a distribution. To further describe shape, we can compute sample skew and kurtosis to measure asymmetry and extreme values.

There are many other statistics we could compute on an ad-hoc basis. However, shape is often best understood with graphical descriptions: histogram, ECDF, Boxplot. These should be made before numerical descriptions: skewness and kurtosis statistics.

The skewness statistic captures how asymmetric the distribution is by measuring the average cubed deviation from the mean, normalized the standard deviation cubed \[\begin{eqnarray} \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} [\hat{X}_{i} - \hat{M}]^3 / n}{ \hat{S}^3 } \end{eqnarray}\]

X <- USArrests[,'Murder']

hist( X^2, border=NA,

xlab='[Murder Rate]^2',

main=NA, freq=F, breaks=20)

skewness <- function(X){

X_mean <- mean(X)

m3 <- mean((X - X_mean)^3)

s3 <- sd(X)^3

skew <- m3/s3

return(skew)

}

skewness( X^2 )

## [1] 1.078254

skewness( X^3 )

## [1] 1.658012We can automatically compare against the normal distribution, which has a skew of 0.

This statistic captures how many “outliers” there are like skew but looking at quartic deviations instead of cubed ones. \[\begin{eqnarray} \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n} [\hat{X}_{i} - \hat{M}]^4 / n}{ \hat{S}^4 }. \end{eqnarray}\] Some authors further subtract \(3\) to explicitly compare against the normal distribution (the normal distribution has a kurtosis of \(3\)).

Boxplot whiskers are a great way to examine kurtosis, with more circle ``outliers’’ indicating more kurtosis. You can also see skew in the boxplot when one quartile is much further from the median than the other.

X1 <- X^1/mean(X^1)

X2 <- X^2/mean(X^2)

X3 <- X^3/mean(X^3)

X4 <- X^4/mean(X^4)

boxplot(X1, X2, X3, X4,

names=c(1,2,3,4), xlab='Data Transformations',

main=NA)

kurtosis <- function(X){

X_mean <- mean(X)

m4 <- mean((X - X_mean)^4)

s4 <- sd(X)^4

kurt <- m4/s4

return(kurt)

# use instead to compare against normal

# excess_kurt <- kurt - 3

}

kurtosis( X1 )

## [1] 2.05077

kurtosis( X2 )

## [1] 3.247877

kurtosis( X3 )

## [1] 5.166225

kurtosis( X4 )

## [1] 7.511867You can also describe distributions in terms of how clustered the values are, including the number of modes, bunching, and many other statistics. But remember that “a picture is worth a thousand words”.

Transformations can stabilize variance, reduce skewness, and make model errors closer to Gaussian.

Perhaps the most common examples are power transformations: \(y= x^\lambda\), which includes \(\sqrt{x}\) and \(x^2\).

Other examples include the exponential transformation: \(y=\exp(x)\) for any \(x\in (-\infty, \infty)\) and logarithmic transformation: \(y=\log(x)\) for any \(x>0\).

The Box–Cox Transform nests many cases used by statisticians. For \(x>0\) and parameter \(\lambda\), \[\begin{eqnarray} y=\begin{cases} \dfrac{x^\lambda-1}{\lambda}, & \lambda\neq 0,\\ \log\left(x\right) & \lambda=0. \end{cases} \end{eqnarray}\] This function is continuous over \(\lambda\).

# Box–Cox transform and inverse

bc_transform <- function(x, lambda) {

if (any(x <= 0)) stop("Box-Cox requires x > 0")

if (abs(lambda) < 1e-8) log(x) else (x^lambda - 1)/lambda

}

bc_inverse <- function(t, lambda) {

if (abs(lambda) < 1e-8) exp(t) else (lambda*t + 1)^(1/lambda)

}

X <- USArrests[,'Murder']

hist(X, main='', border=NA, freq=F)

par(mfrow=c(1,3))

for(lambda in c(-1,0,1)){

Y <- bc_transform(X, lambda)

hist(Y,

main=bquote(paste(lambda,'=',.(lambda))),

border=NA, freq=F)

}

Be careful about transforming your data, as the interpretation can be harder.

The mean of transformed data is not equivalent to transforming the mean, for example, which is one reason why you want to first summarize your data before transforming it.

We can actually say more about how the mean of transformed data not equivalent to transforming the mean. To do that, we define two types of functions:

Let \(\hat{Y}_{i}=g( \hat{X}_{i})\), and denote the mean as \(\hat{M}_{Y}\).

If \(g\) is a concave function, then \(g( \hat{M}_{X} ) \geq \hat{M}_{Y}\).

If \(g\) is a convex function, then the inequality reverses: \(g( \hat{M}_{X}) \leq \hat{M}_{Y}\).

mean( exp(x) )

## [1] 10.06429

exp( mean(x) )

## [1] 7.389056