Code

# Bivariate Data from USArrests

xy <- USArrests[,c('Murder','UrbanPop')]

colnames(xy) <- c('y','x')

xy0 <- xy[order(xy[,'x']),]Understanding whether we aim to describe, explain, or predict is central to empirical analysis. The three distinct purposes are to accurately describe empirical patterns, explain why the empirical patterns exist, predict what empirical patterns will exist.

| Objective | Core Question | Goal | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Describe | What is happening? | Characterize patterns & facts | Summary stats, visualizations, correlations |

| Explain | Why is it happening? | Establish causal relationships & mechanisms | Theoretical models; experimentation; counterfactual reasoning |

| Predict | What will happen? | Anticipate outcomes; support decisions that affect the future | Machine learning, treatment effect forecasting, policy simulations |

Here is an example for minimum wages.

The distinctions matter, as they help you recognize that predictive accuracy or good data visualization does not equal causal insight. You can then better align statistical tools with questions. Try remembering this: Describe reality, Explain causes, Predict futures

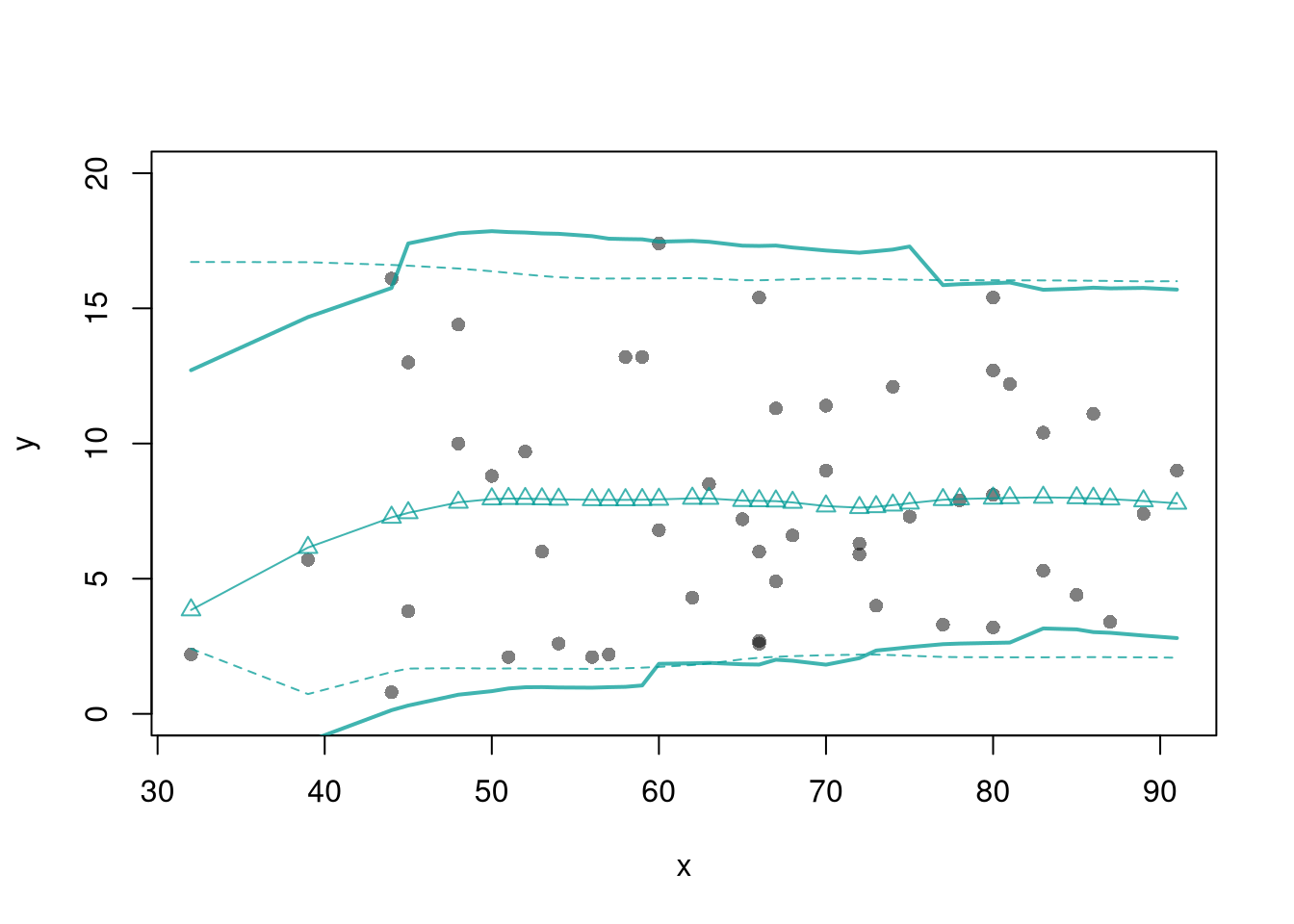

Here, we consider a range for \(Y_{i}\) rather than for \(m(X_{i})\). These intervals also take into account the residuals, the variability of individuals rather than the variability of their mean.

# Bivariate Data from USArrests

xy <- USArrests[,c('Murder','UrbanPop')]

colnames(xy) <- c('y','x')

xy0 <- xy[order(xy[,'x']),]For a nice overview of different types of intervals, see https://www.jstor.org/stable/2685212. For an in-depth view, see “Statistical Intervals: A Guide for Practitioners and Researchers” or “Statistical Tolerance Regions: Theory, Applications, and Computation”. See https://robjhyndman.com/hyndsight/intervals/ for constructing intervals for future observations in a time-series context. See Davison and Hinkley, chapters 5 and 6 (also Efron and Tibshirani, or Wehrens et al.)

# From "Basic Regression"

xy0 <- xy[order(xy[,'x']),]

X0 <- unique(xy0[,'x'])

reg_lo <- loess(y~x, data=xy0, span=.8)

preds_lo <- predict(reg_lo, newdata=data.frame(x=X0))

# Jackknife CI

jack_lo <- sapply(1:nrow(xy), function(i){

xy_i <- xy[-i,]

reg_i <- loess(y~x, dat=xy_i, span=.8)

predict(reg_i, newdata=data.frame(x=X0))

})

boot_regs <- lapply(1:399, function(b){

b_id <- sample( nrow(xy), replace=T)

xy_b <- xy[b_id,]

reg_b <- lm(y~x, dat=xy_b)

})

plot(y~x, pch=16, col=grey(0,.5),

dat=xy0, ylim=c(0, 20))

lines(X0, preds_lo,

col=hcl.colors(3,alpha=.75)[2],

type='o', pch=2)

# Estimate Residuals CI at design points

res_lo <- sapply(1:nrow(xy), function(i){

y_i <- xy[i,'y']

preds_i <- jack_lo[,i]

resids_i <- y_i - preds_i

})

res_cb <- apply(res_lo, 1, quantile,

probs=c(.025,.975), na.rm=T)

# Plot

lines( X0, preds_lo +res_cb[1,],

col=hcl.colors(3,alpha=.75)[2], lt=2)

lines( X0, preds_lo +res_cb[2,],

col=hcl.colors(3,alpha=.75)[2], lty=2)

# Smooth estimates

res_lo <- lapply(1:nrow(xy), function(i){

y_i <- xy[i,'y']

x_i <- xy[i,'x']

preds_i <- jack_lo[,i]

resids_i <- y_i - preds_i

cbind(e=resids_i, x=x_i)

})

res_lo <- as.data.frame(do.call(rbind, res_lo))

res_fun <- function(x0, h, res_lo){

# Assign equal weight to observations within h distance to x0

# 0 weight for all other observations

ki <- dunif(res_lo[['x']], x0-h, x0+h)

ei <- res_lo[ki!=0,'e']

res_i <- quantile(ei, probs=c(.025,.975), na.rm=T)

}

res_lo2 <- sapply(X0, res_fun, h=15, res_lo=res_lo)

lines( X0, preds_lo + res_lo2[1,],

col=hcl.colors(3,alpha=.75)[2], lty=1, lwd=2)

lines( X0, preds_lo + res_lo2[2,],

col=hcl.colors(3,alpha=.75)[2], lty=1, lwd=2)

# Bootstrap Prediction Interval

boot_resids <- lapply(boot_regs, function(reg_b){

e_b <- resid(reg_b)

x_b <- reg_b[['model']][['x']]

res_b <- cbind(e_b, x_b)

})

boot_resids <- as.data.frame(do.call(rbind, boot_resids))

# Homoskedastic

ehat <- quantile(boot_resids[,'e_b'], probs=c(.025, .975))

x <- quantile(xy[,'x'],probs=seq(0,1,by=.1))

boot_pi <- coef(reg)[1] + x*coef(reg)['x']

boot_pi <- cbind(boot_pi + ehat[1], boot_pi + ehat[2])

# Plot Bootstrap PI

plot(y~x, dat=xy, pch=16, main='Prediction Intervals',

ylim=c(-5,20), font.main=1)

polygon( c(x, rev(x)), c(boot_pi[,1], rev(boot_pi[,2])),

col=grey(0,.2), border=NA)

# Parametric PI (For Comparison)

#pi <- predict(reg, interval='prediction', newdata=data.frame(x))

#lines( x, pi[,'lwr'], lty=2)

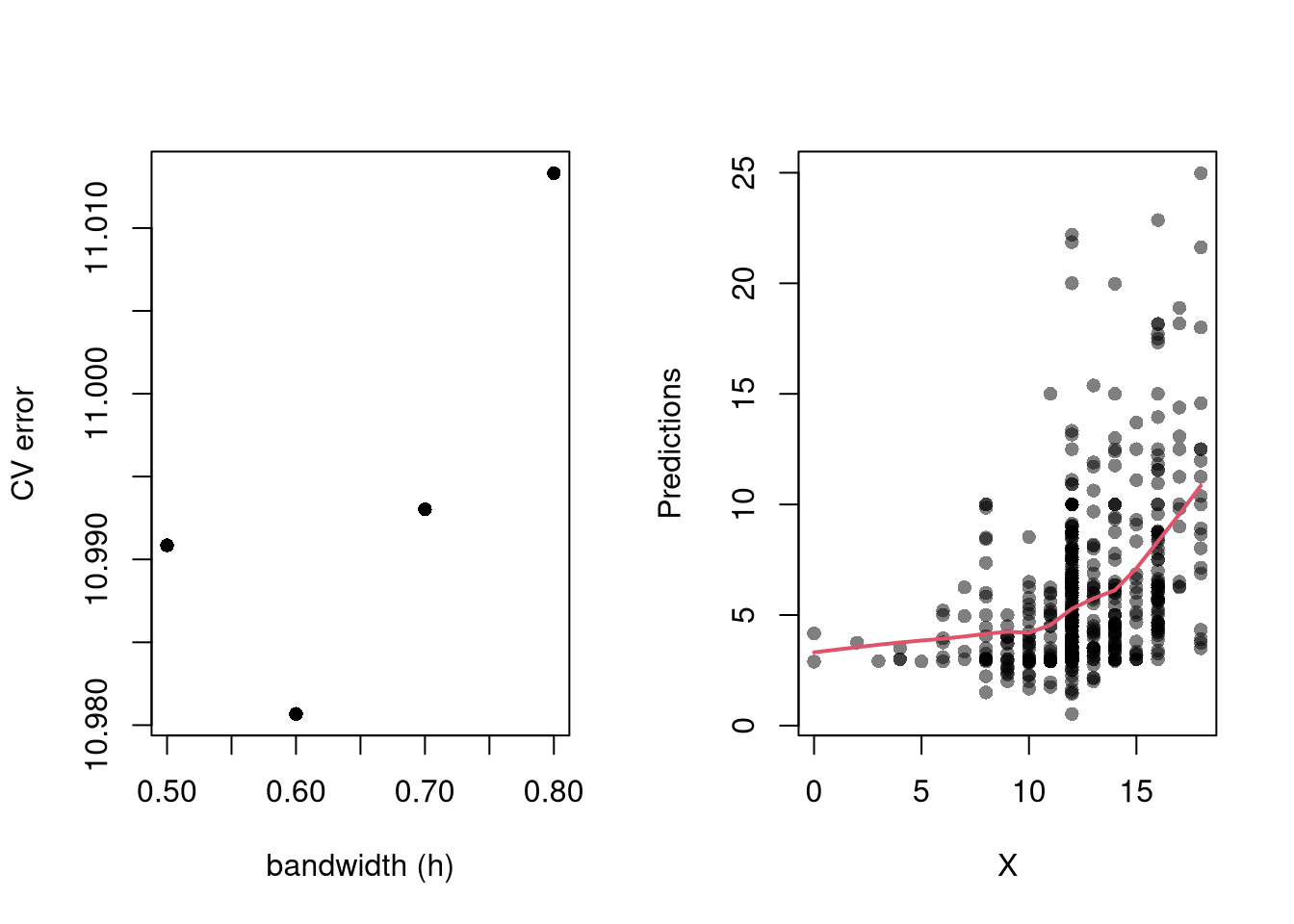

#lines( x, pi[,'upr'], lty=2)Perhaps the most common approach to selecting a bandwidth is to minimize error. Leave-one-out Cross-validation minimizes the average “leave-one-out” mean square prediction errors: \[\begin{eqnarray} \min_{h} \quad \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \left[ \hat{Y}_{i} - \hat{y_{[i]}}(X,h) \right]^2, \end{eqnarray}\] where \(\hat{y}_{[i]}(X,h)\) is the model predicted value at \(X_{i}\) based on a dataset that excludes \(X_{i}\), and \(h\) is the bandwidth (e.g., bin size in a regressogram).

Minimizing out-sample prediction error is perhaps the simplest computational approach to choose bandwidths, and it also addresses an issue that plagues observational studies in the social sciences: your model explains everything and predicts nothing. Note, however, minimizing prediction error is not objectively “best”.

library(wooldridge)

# Crossvalidated bandwidth for regression

xy_mat <- data.frame(x1=wage1[,'educ'],y=wage1[,'wage'])

## Grid Search

BWS <- c(0.5,0.6,0.7,0.8)

BWS_CV <- sapply(BWS, function(h){

E_bw <- sapply(1:nrow(xy_mat), function(i){

llls <- loess(y~x1, data=xy_mat[-i,], span=h,

degree=1, surface='direct')

pred_i <- predict(llls, newdata=xy_mat[i,])

e_i <- (pred_i- xy_mat[i,'y'])

return(e_i)

})

return( mean(E_bw^2) )

})

## Plot MSE

par(mfrow=c(1,2))

plot(BWS, BWS_CV, ylab='CV error', pch=16,

xlab='bandwidth (h)',)

## Plot Optimal Predictions

h_star <- BWS[which.min(BWS_CV)]

llls <- loess(y~x1, data=xy_mat, span=h_star,

degree=1, surface='direct')

plot(xy_mat, pch=16, col=grey(0,.5),

xlab='X', ylab='Predictions')

pred_id <- order(xy_mat[,'x1'])

lines(xy_mat[pred_id,'x1'], predict(llls)[pred_id],

col=2, lwd=2)